>

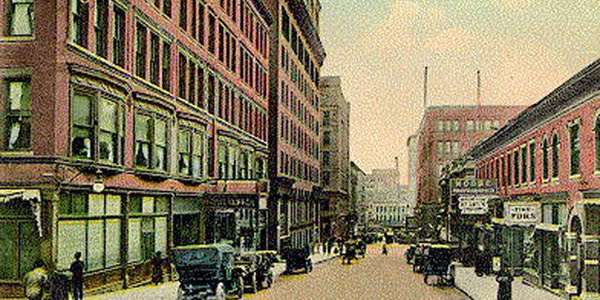

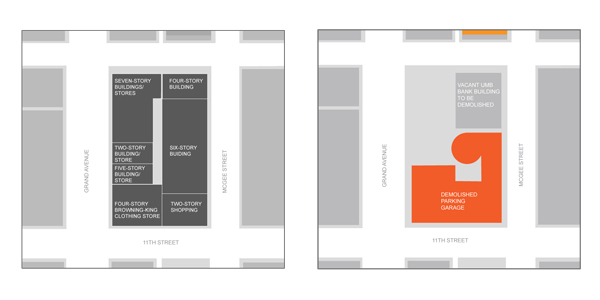

A century ago, the block between Grand and McGee on 11th Street was a shining example of Kansas City’s dynamic, pedestrian-friendly urban retail corridors. Filled with street-level shops of all types, the block provided an enjoyable and ever-changing experience for the urbanite. The block charted the optimistic character of a growing consumer culture, celebrating the shifting needs and desires of the populace.

In the 1920’s, the shopping experience was transforming from a personal, practical need to a spectacular social event, and this city block was responsive to the changing culture.

The Browning King’s clothing store posted World Series results on its streetfront billboard, attracting crowds of lingering sports fans.

Moore-Photographs store, Rompel Art Co. Picture Framing and Fine Furs on 11th Street were busily frequented by shoppers and traveling patrons. Their modernizing practices amplified the energy of their clientele, with pulsing cycles of merchandise delivery, window displays, and storefronts.

The six-story Kupper Hotel hosted out-of-town shoppers, wishing to stay overnight after short-stay shopping trips to the surrounding area.

Shopping was becoming the definitive urban activity, to be experienced within tightly controlled environments, and tightly controlled timeframes. With each subsequent visit to this evolving urban environment, the shopper’s experience and expectations were re-invented anew.

With the increasing economy and ease of personal travel offered by the automobile, the block became even more conducive to this instant commercial gratification, accelerating the speed and frequency of each shopper’s visits. It soon became apparent that, in order to facilitate the increasing speed of commerce, the physical fabric of the block itself would need to change.

The entire block was demolished.

A new, seven-story parking structure went up in its place.

The Shoppers Parkade, completed in 1969, embodied the new form of commercial urbanism. Supplying easy access to the new urban shoppers and their automobiles, the Parkade also provided the very retail environments that were their draw, incorporating shops under the parking deck at street level.

The same forces that catalyzed such a hyperbolic conception of life as an urban commuter would soon lead to its decay. By facilitating competition, market pressures, and planned obsolescence, projects like the Parkade made it possible for retail hubs to emerge throughout the city. Easy access and unchecked speed were the new paradigm, and shoppers would seek out the biggest, newest, and most convenient area to spend their time and money. The shopping center was decentralized.

Soon, the shopping district at 11th and Grand, and the Shopper’s Parkade, lost their appeal. The multi-story parking deck stood vacant, with high levels of crime and drug-dealing hosted in the shadows of its dark ramps.

—

After years of neglect and concern, its is time once again to re-imagine the block.

The Downtown Development Group, a chapter of the Downtown Council of Kansas City, decided to demolish the Shopper’s Parkade, at a cost of almost $1.4 million, partly borrowed from federal loans and partly from city funds.

In its place will be a surface parking lot.

Demolition is well underway, and the effect on the urban fabric of the area is already clear. In a race to increase the speed and ease of access to the area, the very reasons for that speed and ease are obliterated. Replacing shops with parking decks, and parking decks with surface lots, the city has cannibalized its core.

By so emphatically embracing the logics of commerce in the conception of public space, the experience of the city is subject to the whims of the market. In the current economic environment, investment in a surface parking lot has substantial security, especially compared to other, more risky ventures like commercial or residential development. Paradoxically, as the city seeks to enable growth and facilitate access, it is investing in its own destruction.

The city must imagine a new relationship with commerce, and automobile culture, if it is to survive as a viable living environment, and a desired commercial destination. As consumer culture shifts its focus from goods to services and beyond, the city too must respond in kind.

This article originally appeared on kcfreepress.com.